| Mine To Die - Prologue |

Here is the Prologue to ‘Mine to Die’, my latest work, published in February 2024.

“Feelings of trepidation and excitement – that’s a good blend for starting a book. I do know, after all, where I am going. Underground. Under the surface of things. And I am starting with an overture.

An overture is something offered to open the way to some conclusion. The word ‘overture’ comes to us from the Old French overture, meaning ‘opening; proposal’. This Old French word is rooted in the Latin apertura, meaning ‘opening’, from aperire, ‘to open, uncover’. There we have it. Open, and under we go. My task is to create a book that will be called ‘Mine to Die’ and in it I shall offer an account of the industrial revolution that transformed the landscape in one county of England, Cornwall, through mining the ground under its surface.

You will find that each section of my book also begins with an overture, a page or more of source material for you to read and make your own interconnections before taking on board the commentary that follows.

All will become clear. Trust me, if you dare – I am a maker of magic; a wordsmith intent on offering the reader my take on our history over the last 250 years. A magician who is a qualified historian. I know my trade. I weave my tales of understanding through the selection of data I call facts – and so they are, no matter how random their pathway to my being. You, however, are your own historian too. You can choose to create your own tapestry of interpretations. But please keep an open mind. Humility is a virtue for those who follow the trade of history making.

When I became a teenager around sixty years ago, I acquired a book that claimed to tell the History of England. I still have the volume. In it, industrialisation is presented as an agency for welfare, serving to nourish and clothe the people. That is very far from being the whole truth, as the analysis in my book will show. Industrialisation brought sickness, injury, and death, too.

I want to weave a tale in these pages that will draw you into what I consider a most absorbing and important question. I promise you a novel kind of history making and telling but I will be frank. In the end, I am hoping you will make a judgement call in favour of life and against the unregulated pursuit of profit when faced with this ethical question:

‘Should the pursuit of profit ever be at the expense of health, well-being, and life itself?’

These concerns could not be more vital. The industrial revolution that began a quarter of a millennium ago in Britain now threatens to extinguish our global existence as a species.

|

|

| Botallack - West Wheal Owles Mine |

| |

|

|

| Mine To Die - Overture |

For now, in this Overture, let me introduce you to how I will present my truth in this book.

The 19th and 20th century broadsheet newspapers which I have been reading will be one of my important sources. They had the space for the editors to publish much of the copy produced by reporters at public meetings. These reporters were good at recording the words of participants. I have found this factual record illuminating.

The story I weave through time – from the late 19th century through to the killing fields of the first world war and then through to the last years of the second world war – will have a local Cornish focus but it will serve as a study in microcosm of what has been happening in capitalist industrial societies over the last 250 years: the pursuit of profit by the few at the expense of the health and well-being of the masses.

Such wording risks being too simplistic; the analysis needs more subtlety - but at times it comes down to that sort of ruthless focus.

My book is divided into sections, many of which begin with newspaper stories taken from the resources of The British Newspaper Archive (BNA). This is free to search in the British Library reading rooms but has also been made available to read online at home.

The teams of people who have been employed to digitise individual newspaper pages come at a cost and I have paid my subscription to gain full access. I did so when I was alerted in the autumn of 2021 to the news that copies of The Cornish Post and Mining News, published from 1889 to 1944 in Camborne, the centre of the Cornish mining industry, had been digitalised and were now available.

At that moment, the idea for this book began to germinate. And I soon discovered my searches were yielding rich data from other publications too. This idea of mine was bearing fruit. I knew now that this would be a book worth reading.

Here is the first of my sections, with its sources presented and acknowledged, followed by my commentary. The Overture has concluded; the journey begins.”

|

|

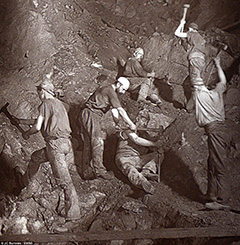

| Cornish Tin Miners In The 1890s |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Cornwall Tin Miners -

Cook's Kitchen Mine In The1890s |

| |

| Early Reviews |

| |

‘The quotations are powerful, the naming of the frequently dead makes the record audible. Donovan’s argument is sustained, angry at times, wistful at others. Mine to Die hints at a refrain belonging on the lips of the Cornish poor, tin miners in peacetime, trench builders in wartime, but in both their fated or preordained lot: to die. Mine to Die implies that, with a change of moral perspective in the hearts of the wealthy and powerful, there might have survived a mine – to live.’

(Bishop Dr Bill Musk) |

| |

‘Mine to Die’ is an important book that I’ve read with great interest. It successfully combines historical analysis with ethical enquiry. Should, Rob Donovan asks, profit-making be pursued at the expense of the safety and health of working people? That the healthy life of nineteenth-century Cornish tin-miners typically extended to only 28 years old, even if they avoided the underground disasters that were all too frequent, is just one of the telling pieces of evidence with which the author answers the question in the negative. It is an answer that, while in the first instance focused on Cornwall, also self-evidently has a much broader compass as we face up to a world in which inequality and climate deterioration have become inseparable’.

(Professor John Reid) |

| |

‘I was struck by the author’s ability to handle rigorous academic, resource-based, research with a strong personal almost passionate take without compromising the integrity/objectivity of the documentary sources – and then, impressively, the way in which the relationship between global and national events hit the everyday working lives of the Cornish miners and their families. This becomes a strong polemic against the artificial construct of unfettered capitalism where greed seems to win so consistently against the actual need and dignity of work.

(Alan Carter, former university Dean) |

| |

|